Site will be

unavailable for maintenance from June. 4, 11:30 p.m., to June 5, 12:30 a.m. ET. Thank you for your

patience!

Choose Your Giving Adventure.

Around the world, children are exposed to hardships that no child should ever have to face. Your donation to ChildFund helps connect children in 23 countries to everything they need for a strong start in life, like nutritious meals, clean water, access to education and healthcare, protection from violence and more. Explore how you can provide immediate support and join us in changing – and saving – lives!

More Ways to Give

-

Give Monthly

Join the ChildFund Village and see the impact you’ll make for children around the globe.

-

Sponsor a Child

Connect with a child and become a source of hope, encouragement and support.

-

Emergency Response

Help us respond to children’s most urgent needs when disaster strikes.

-

Gift Catalog

Every physical gift you choose from our catalog means the world to a child.

-

Draw for Hope

Your gifts can give a child the power to create their future.

-

Matching Gifts

Make double the impact when your gift is matched by your employer.

-

Corporate Giving

Learn how your company can contribute to a better future for kids.

-

Philanthropy

Explore unique opportunities to fund life-changing projects and programs.

-

Planned Giving

Leave a legacy that will touch generations.

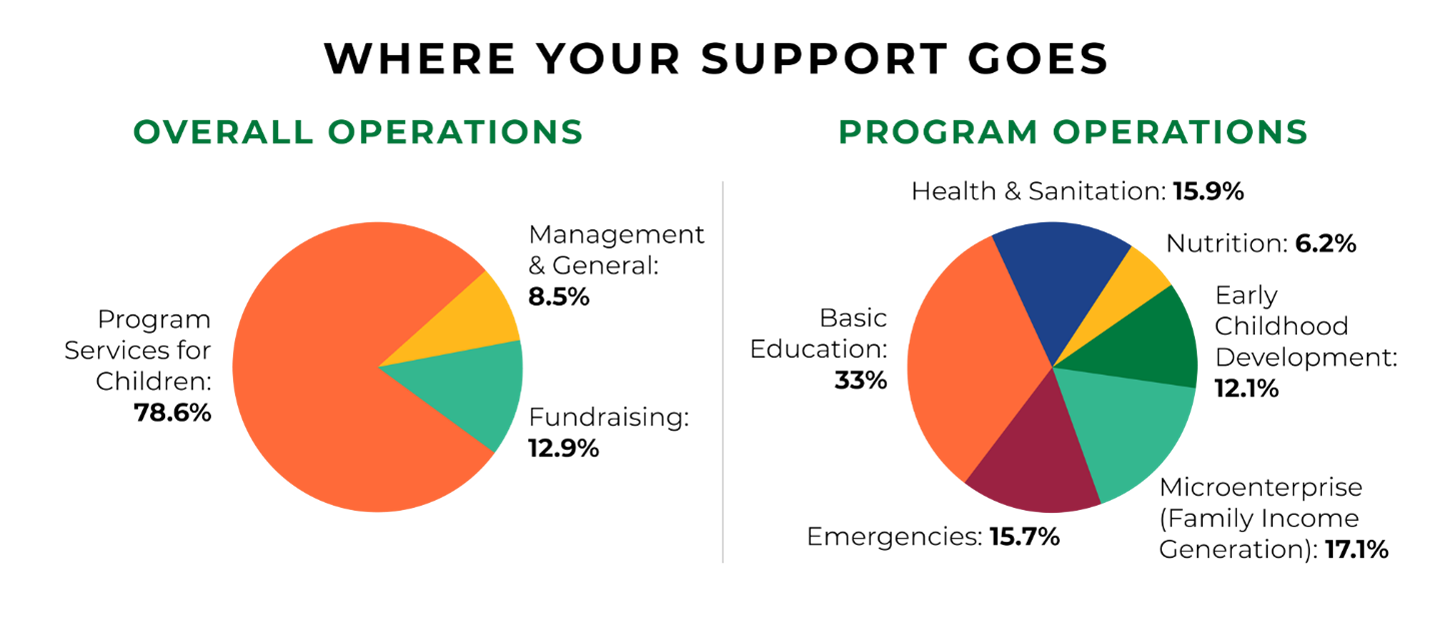

Change You Can See.

When you donate to children, you’re making an investment in the future of our planet – and every penny counts. We’re proud to be a top-rated charity with a 4-star rating from Charity Navigator, and we received the Platinum Charity Seal in 2023 from Candid. Want to learn more? Dive deep into how we’re accountable to you, our amazing supporters.