Site will be

unavailable for maintenance from June. 4, 11:30 p.m., to June 5, 12:30 a.m. ET. Thank you for your

patience!

Child protection data illuminates a path forward for children in crisis

Posted on 06/18/2025

In any crisis, children stand at the crossroads of vulnerability and resilience. They are often the first to suffer – yet their needs, fears and hopes are as diverse as the communities they live in. That’s why ChildFund uses a hyper-localized, human-centered approach to program design – one that listens first, then acts, ensuring that every intervention is rooted in the lived experiences of children, their families and communities.

Take Mozambique, for example – a nation in southeastern Africa that has weathered a relentless storm of environmental disasters, conflict and disease in recent years. According to a 2024 UNICEF report, 3.4 million children there urgently need humanitarian assistance.

Belissa, 7, in Mozambique.

In certain provinces of the country, children and families haven’t been able to catch a break. Beginning in 2016, families in Mozambique found themselves in the midst of a crippling national debt crisis, causing prices of food and ordinary goods to soar. Shortly after, violent conflict began to break out in the north of the country, with armed insurgents attacking towns, burning homes and causing widespread displacement. Then there was the COVID-19 pandemic. Through it all, multiple droughts, cyclones and other natural disasters have periodically shattered communities, tearing through any financial stability families have been able to build.

Children attend remedial classes as part of ChildFund and WeWorld's emergency response efforts after Cyclone Chido in December 2024. The response supported more than 50,000 people whose lives had been uprooted by the storm.

In highly complex contexts like these, where children are facing multidimensional risks to their well-being – not only extreme poverty, but also violence, displacement, educational barriers and the developmental repercussions of all those harms – it’s critical to ensure that the support they receive is multidimensional, too. Community-based child protection mapping (CBCPM) can be an immensely valuable tool for exactly that reason, allowing us to work directly with children and families in vulnerable situations to co-discover where and how they need support most.

Community-based child protection mapping method and results

Between May and September 2023, ChildFund and our partner organization WeWorld conducted a CBCPM activity in four districts of Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province to identify child protection concerns and issues. The exercise began with training a team of research consultants and culminated in a variety of activities that would come to guide ChildFund’s program development in the area.

Working directly with children and families, we used Action Participatory Research Tools that were child-friendly – for example, art , community discussions and surveys – to learn more not only about the issues themselves, but also about how children and families are responding to them and building resilience in the face of adversity.

Overall, the goal of our research was to learn …

- What is the emergency or humanitarian context?

- Who are the main groups of vulnerable children in the community?

- What are the harms/risks that vulnerable children face in the community? Are there any specific harms that are exacerbated following the emergency events?

- What coping strategies and strengths (i.e. resilience, skills and participation) do children and community members use to deal with risks and adversity?

- What response and service delivery mechanisms exist in the community? (i.e. safe spaces, practices, protective structures, service providers — that is, health, legal, case management, mental health and psychosocial support services — and formal and informal protection mechanisms)

We surveyed a total of 261 participants – a mixture of children, youth and adults. The findings were illuminating.

First, the community identified the primary challenges they had faced in the last several years – including war and terrorism (since 2017), the Kenneth cyclone (since 2019), COVID-19 (since 2020) and recurring disease outbreaks like cholera, diarrhea and malaria.

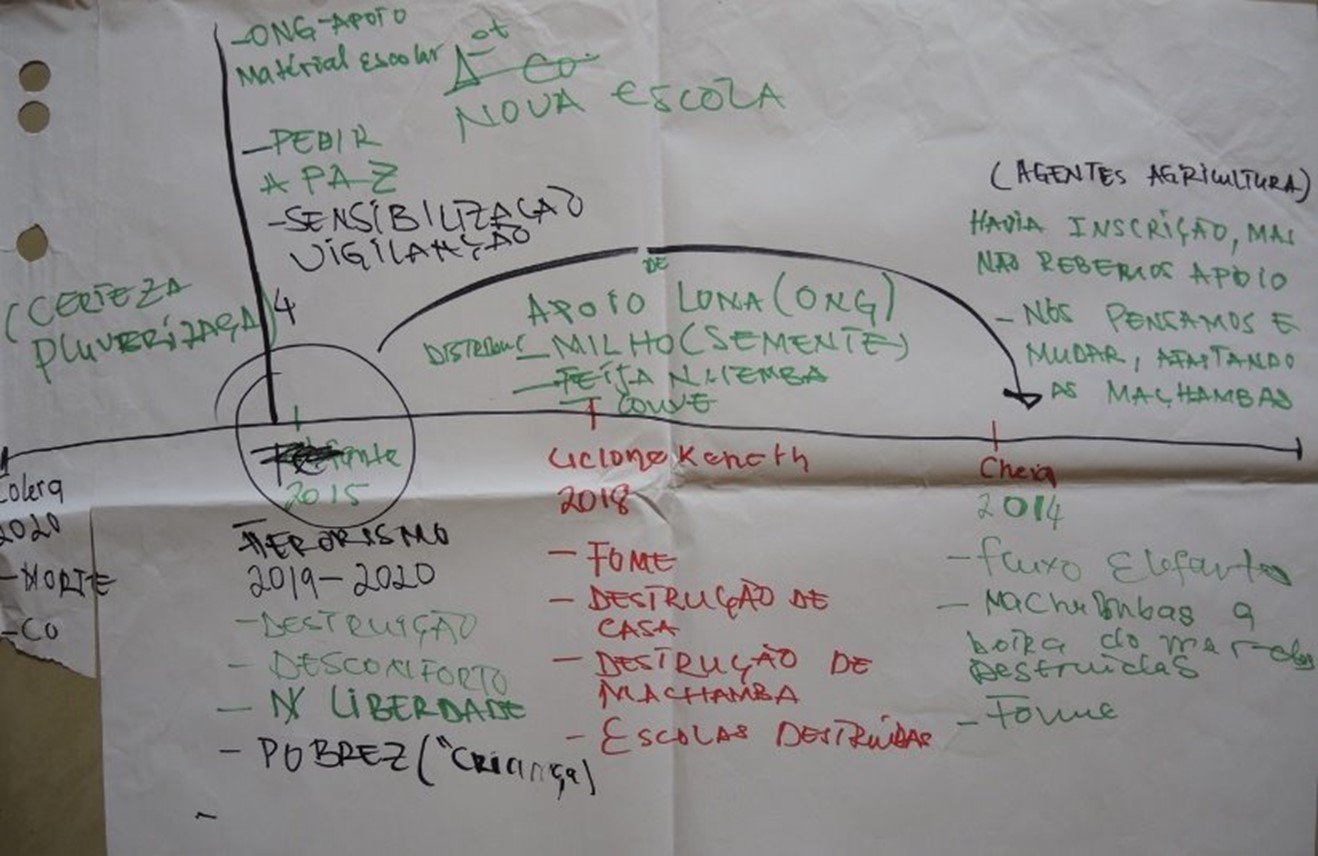

Adult community members developed this “timeline of challenges” during a CBCPM event to map out the hardships they have faced together during the past several years.

Adult community members developed this “timeline of challenges” during a CBCPM event to map out the hardships they have faced together during the past several years.

What do all these challenges look like through a child’s eyes? The picture is quite different from how adults see the problems. Often, children talked about experiencing violence in their homes – a direct result of caregivers wrestling with stress. They talked about feeling overburdened by house chores, struggling to access basics like clean water and school, and fearing physical and sexual violence.

Moreover, children, youth and community members alike reported little knowledge of how to report violence against children. “Where are you going to report it?” said one community member. “It is not possible to report. Adolescents only make comments to their friends, but not to community structures.”

In one activity, we asked children what makes them happy and what makes them sad. “I get sad when I have to carry a big bucket full of water,” said one 14-year-old girl. “My neck hurts. The big bucket weighs a lot until I get home. I've already broken two buckets because I couldn't carry them, and my mother hit me a lot and I cried a lot, and I was really sad.”

In one activity, we asked children what makes them happy and what makes them sad. “I get sad when I have to carry a big bucket full of water,” said one 14-year-old girl. “My neck hurts. The big bucket weighs a lot until I get home. I've already broken two buckets because I couldn't carry them, and my mother hit me a lot and I cried a lot, and I was really sad.”

We learned that among the most vulnerable children were those who had been displaced and those with disabilities, as well as children who were out of school or without parental care – and of course, there was plenty of overlap among these categories. Adolescent girls were at particular risk of child protection concerns like early marriage.

“I drew a pregnant girl with a baby on her back,” said one 14-year-old boy. “Parents force them to get married early, and girls drop out of school.”

“I drew a pregnant girl with a baby on her back,” said one 14-year-old boy. “Parents force them to get married early, and girls drop out of school.”

We did not, however, seek to learn only about problems. We also identified children’s coping strategies and strengths. One response that stood out as a common protective factor was social connection, specifically in the form of peer, sibling and parent-child relationships. These findings are consistent with peer-reviewed research that points to the stress-reducing benefits of social support, especially for the developing child.

Children and families also reported that receiving advice on positive parenting and relationships – say, in the form of community discussions – helped them feel supported and capable of handling life’s challenges.

Finally, we asked children to tell us about some safe and unsafe places in their community. The most common response was that the same place could be safe or unsafe at different times, depending on the context.

“I drew a hospital because every time I get sick, I go there, and they give me medicine and I feel better,” said one 16-year-old.

“I drew a hospital because every time I get sick, I go there, and they give me medicine and I feel better,” said one 16-year-old.

“I'm happy at school, because I study and I talk to friends,” said one adolescent boy. “When I'm at school, I feel good.”

“I'm happy at school, because I study and I talk to friends,” said one adolescent boy. “When I'm at school, I feel good.”

Leading program design with community-based child protection mapping

Knowledge is power – and by collecting clear, cohesive data on the issues facing children in each particular region where we work, we can create a detailed picture of their needs that directly guides program development. We then tailor each of these programs to the context of children in that particular community to ensure that we’re making maximum impact.

Based on our research, we came up with a few recommendations for program delivery in the communities of Cabo Delgado. We now aim to …

- Design and implement a Social and Behavior Change Communication package (including radio drama and radio programs, community theater, community dialogues, etc.) to create awareness among both displaced populations and host communities on child protection issues, to create demand for available child protection services, and to promote social cohesion (in other words, the inclusion of people who are displaced, people with disabilities, children without parental care, girls and other marginalized groups).

- Activate (or reactivate) Community Child Protection Committees and ensure that they have adequate knowledge, skills and resources to work properly.

- Train service providers (police, health professionals, social workers) and local leaders to avoid discriminatory and paternal attitudes and suggest private resolutions of violations.

Useful as it may be for data collection purposes, CBCPM goes further than just conducting basic surveys. ChildFund’s unique localization strategy, effectively implemented in this highly complex humanitarian context, allowed us to successfully design a program tailored to community needs. This approach involved working closely with relevant authorities and stakeholders at multiple levels, from the community level to local and international actors. Direct community engagement further increased accessibility and acceptability, ensuring the programs effectively met the needs of children and youth.

Ligia Macalo is a Project Mobilizer with Associação Txivuno Txavanana (ATTV), ChildFund’s local partner in Zavala District, Mozambique, where our Community-Based Child Protection Mechanism project is now implemented. Here, she conducts an awareness session for parents on early marriage and children’s rights.

Ligia Macalo is a Project Mobilizer with Associação Txivuno Txavanana (ATTV), ChildFund’s local partner in Zavala District, Mozambique, where our Community-Based Child Protection Mechanism project is now implemented. Here, she conducts an awareness session for parents on early marriage and children’s rights.

Through that process of engagement, we can begin truly nurturing the relationships with communities, families and other stakeholders that will assist children build resilience over the long term. It is through this trust and sense of mutual understanding and support that people become better able to weather life’s many storms – even those facing the most formidable challenges of all.

Dive deeper with ChildFund's Community-Based Child Protection Mapping Guidance — including tools.

Loading...